Despite long-standing international perceptions of Alberta’s oil sands as a sprawling industrial wasteland visible from space, new research reveals the vast majority of the region remains in good health — ecologically speaking.

According to a new report from the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI), just 2.6% of Alberta’s oil sands region was directly affected by energy development as of 2021 even though the oil sands cover about 142,000 square kilometres of boreal forest — an area nearly the size of Montana.

“There’s a mistaken perception that the oil sands region is one big strip mine, and that’s simply not the case,” said David Roberts, director of the ABMI’s science centre told the Canadian Energy Centre. “The energy footprint is tiny in the total area once you zoom out to the boreal forest surrounding this development.”

The ABMI is an independent scientific agency responsible for monitoring environmental health in Alberta’s oil sands using a rigorous, data-driven approach rooted in globally accepted scientific standards.

Its newly released Status of Land Cover and Biodiversity in the Oil Sands Region report is one of the most detailed assessments to date of how land use is affecting biodiversity in the area.

The findings stand in sharp contrast to previous claims from environmental groups such as Greenpeace, which once stated that oil sands operations had disturbed an area the size of the United Kingdom or the state of Florida.

While such sensationalized statements have attracted international media attention, ABMI’s data shows a much more nuanced and fact-based picture.

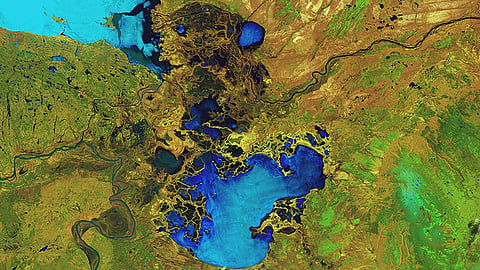

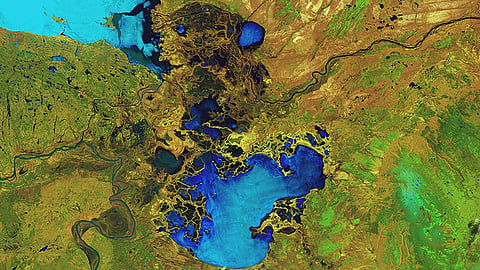

Using satellite imagery, LiDAR (light detection and ranging), and field data from 328 monitoring sites across the Athabasca, Cold Lake, and Peace River oil sands regions, the study tracked changes in land cover and habitat from 2000 to 2021.

During that period, the total human footprint — including forestry, agriculture, and municipal uses — rose from 12% to 16.5%. Energy development specifically grew from 1.4% to 2.6% even as oil sands production soared from 667,000 to 3.3 million barrels per day (bpd).

“In general, the effects of energy footprint on habitat suitability at the regional scale were small… for most species because energy footprint occupies a small total area in the oil sands region,” the report notes.

ABMI’s research evaluated the intactness of 719 species of plants, insects, and animals, finding that 87% of their natural habitat remains in a condition suitable to support populations.

The research was commissioned by Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance — the research arm of the Pathways Alliance — a consortium of Canada’s six largest oil sands producers. Roberts says the scope and depth of the report are unmatched.

“We tried to look around when we were asked to put together this report to see if there was a template, but there was nothing — at least nothing from a jurisdiction with significant oil and gas activity,” he said.

“There’s a remarkable level of analysis because of how much data we were able to gather.”

Additionally, 95% of aquatic and wetland habitats and 77% of terrestrial habitats were found to be undisturbed as of 2021.

The report identifies areas for improvement, including the need to address slow vegetation regeneration on seismic lines and the need for better protections for sensitive species like Woodland Caribou.

Still, Roberts emphasized that continued monitoring is essential.

ABMI’s work also involves close partnerships with indigenous communities. A current project with the Lakeland Métis Nation tracks moose populations near in situ oil sand developments, blending traditional Métis knowledge with Western scientific methods.